Goed gespeeld, paps!

Onderstaand artikel is te vinden in het oktober bulletin van de IBPA The International Bridge Press Association.

De International Bridge Press Association (IBPA) staat ten dienste van iedereen die betrokken is bij bridge-media. Door lid te worden, krijg je:

-Toegang tot een groot netwerk van bridgejournalisten en makers van bridge-media uit alle hoeken van de wereld.

– Het maandelijkse IBPA Bulletin, een bridgepublicatie van wereldklasse.

– Toegang tot hoogwaardige foto’s met hoge resolutie.

– Deelname aan de IBPA Awards Ceremony – elk jaar reikt de IBPA prijzen uit in verschillende categorieën. – De winnende journalisten en spelers ontvangen prijzen.

Papa Rombaut wist in Herning als enige van de 21 leiders 12 slagen te halen in 6SA, zoals Guy Dupont hieronder beschrijft.

By Guy Dupont

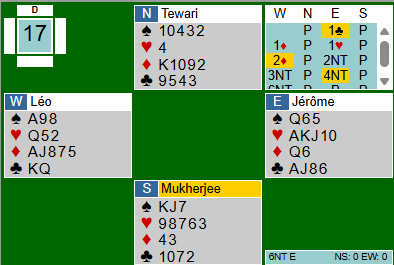

Family partnerships are rare at the highest level of bridge. Husband-wife or sibling pairings are seen more often than parent-child. Jérôme and Léo Rombaut, father (51) and son (21), handle this situation very well. Regulars in the French Open team for several years, they were members of the squad at the last Bermuda Bowl in Herning.

Here is a deal from the second round of the qualifiers, against India, where Jérôme showed exceptional skill in the contract of 6NT. The contract was reached 21 times in the 24-table open event, and he was the only declarer to succeed.

Take Jérôme’s seat as East

South leads the nine of hearts, taken in hand by declarer. The first question: how do you handle the diamonds? Let’s step into the champion’s mind.

If you play the queen, you should be fine on a 3-3 break, but things can go wrong on some 4-2 breaks. If South covers the queen with the king, and you cash the jack, you will be comfortable if the nine or ten has appeared (with South holding king-ten or king-nine doubleton, or North holding a short honour). However, if neither the nine nor ten has appeared by the second round, you will be afraid to play a third diamond – if the suit fails to break 3-3, disaster would follow quickly. Not very appealing.

A more attractive line is to lead a low diamond from dummy toward the queen. That succeeds with diamonds three-three, with king doubleton in the North hand, or in some endgame scenarios against North’s king-fourth. So Jérôme crossed to the king of clubs at trick two and led a low diamond toward his queen, which held. The continuation is almost automatic: unblock the queen of clubs, then play a heart. Surprise! North discards on the second heart. That sheds some light on the situation, but we are far from safe.

At this point we still have some decisions to make: king of spades onside, diamonds three-three, or an elimination ending with a throw-in (for instance, running the eight of spades to force South to lead away from the king). Let’s look at the clues we have seen so far: the absence of a spade lead (the unbid suit) might suggest that South holds the king; and North’s failure to rise with the king of diamonds, combined with his shortage in diamonds, supports the idea that he has four diamonds.

Weighing it all, declarer chose an elimination play, which might end in a throw-in or some squeeze. He cashed a third round of hearts, then the two remaining clubs. The magic six-card ending:

Declarer played the jack of clubs. South, known to have two hearts at this point, is squeezed first. If he discards a spade, declarer can set up a spade. If South parts with a heart, declarer can strip the red cards and play for a throw-in: ace of hearts, diamond to the ace, then run the eight of spades, forcing South to lead away from the king. (If North covers the eight with the ten, the queen loses to the king and declarer finesses the nine on the forced spade return.)

But South found the best defense, discarding the four of diamonds. No matter – now it was North’s turn to be tortured! Declarer discarded a spade from dummy, as did North. Then he cashed the ace of hearts in this position:

On the ace of hearts, another spade from dummy disappeared, and North was doomed. If he threw a spade, declarer could play the ace of spades, leaving North with only diamonds. Then a low diamond would endplay North, forcing a lead away from the king. If instead North discarded a diamond on the ace of hearts, declarer would play ace and another diamond, setting up a diamond trick with the ace of spades as a reentry.

Notice that whatever South chose to discard in the six-card position, the line of discarding one spade from dummy, then another on the ace of hearts, always wins. In the end, once declarer became convinced North held four diamonds, South’s hand no longer mattered. The slam succeeds regardless of the location of the king of spades!

Performing a play like this at your local charity game in Fermant-Clairon would be a significant achievement. How much more satisfying to be the only player in the Bermuda Bowl, the world’s most prestigious championship, to make the slam? In a field of 21 elite declarers, Jérôme could rightly savour a special satisfaction from this unique result.

Marcel Winkel

Marcel Winkel 19-10-2025

19-10-2025